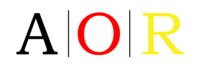

Few people in the entertainment industry grind harder than Abel Tesfaye. As The Weeknd, he was a global pop star by the age of 25, and has earned the right to take his time between projects. But Tesfaye, a true polymath, is overflowing with ideas and has the means to make them real. So a few months before the release of The Idol—the HBO series about a pop star and the cult leader she falls in love with, which Tesfaye cocreated with Reza Fahim and Sam Levinson—he was working until dawn shooting an upcoming movie he cowrote and stars in. When Jeremy O. Harris finally connected with Tesfaye over Zoom, the 33-year-old “nice Canadian guy” had literally just woken up.

ABEL TESFAYE: Big J. What up, bro? Can you hear me?

JEREMY O. HARRIS: Yep. I feel like I look like Tedros [Tesfaye’s character in The Idol] right now.

TESFAYE: [Laughs] Low-key. I literally just woke up.

HARRIS: I woke up at 8 a.m. somehow. It’s like all of my jet lag just has coincided with this day. It’s probably because I was so excited about doing this. And the whole Oscars thing.

TESFAYE: You look East African.

HARRIS: You say that to everyone. You said that to Tyler [Mitchell] too.

TESFAYE: Tyler is absolutely East African. He doesn’t know it, but he’s Ethiopian, without a doubt.

HARRIS: Are you Ethiopian?

TESFAYE: Fully, 100 percent.

HARRIS: That’s wild. The Ghanaian singers I know have this very specific way of singing that engages with the falsetto, and I think it’s because of speaking to their parents in their native tongue. Do you think that Ethiopian has influenced how your voice manifests when you sing as The Weeknd?

TESFAYE: Absolutely. Because if you hear somebody speaking Amharic from miles away, you don’t have to hear the words. All you have to hear is the tone and the frequency, and you’re like, “Those are two Ethiopian aunties talking.” There’s a certain rhythm that you feel and a key that you hit. That was the first language I spoke. And then of course there was Ethiopian music, which was played in our household. It’s in my DNA. You hear it in my music, not literally, but the style and the vibrato, and the way I sing is very unconventional.

HARRIS: I love that. I also love the idea that the language can be understood without seeing the face or the mouth, because that’s how the world first met you. And with each passing year since the first— was House of Balloons [2011] the first mixtape?

TESFAYE: Yeah, but I was trying to make it as a songwriter first. I was writing a lot of demos, very generic pop songs that I was trying to shop to local singers. And then there was this manager I was trying to work with who had “connections” to more famous singers. Nobody wanted it. It just wasn’t conventional like R&B was at the time. And then I tried to be a little bit more experimental to see if people wanted a new sound and nothing was connecting. So I said, “Fuck it. Let me just sing it myself.”

HARRIS: What’s so interesting about that is you were this shadowed figure, and I feel like each passing year you’ve been slowly coming out of the shadow, so that now you’re no longer just The Weeknd, you’re on the cover of this magazine as Abel. Was it hard to take off the mask and step into the light?

TESFAYE: That’s very poetic. I wanted to be very calculated about how I wanted people to see me or hear my music. The initial reason I did that was I didn’t think I was marketable when I was younger, especially for R&B. I didn’t think I had the right look.

HARRIS: What was the right look in your mind? Because you’re a very attractive man.

TESFAYE: Oh, thank you. I think I’ve worked on it more now. [Laughs] The R&B look was very sexual back in the day. Obviously there were a lot of singers that didn’t have the conventional R&B look, but for me it was more of a personal thing. I liked getting an unbiased reaction from my music. People got to just judge me for the art, for the music I was putting out. So it worked in my favor, and then it became a gimmick. No one else was doing it at the time, so it was a breath of fresh air. And then the mythology and the mystique of it ended up becoming as interesting as the music. I tried to ride that wave as much as I could. In the internet age it’s impossible, but I got a few years in.

HARRIS: Right.

TESFAYE: But then I got the Drake cosign and it was getting really overwhelming because everybody was trying to find out who I was and sign me. Everybody was trying to get a piece of it. That part was a little jarring. And then the real challenge was the live performances, going out there and showing yourself to people for the first time. And on top of that, I had to sing, and I had never performed live before, so I got thrown into the fire for that as well. I think Coachella was my first performance in the U.S. and it might have been my fourth performance ever.

HARRIS: Wow. I think I’m the only person who will interview you who’s actually seen The Idol or even been around it, right? Because spoiler, I was going to be in it, but unfortunately there were scheduling conflicts.

TESFAYE: Yeah. I was so heartbroken when you couldn’t make it for that one. We’ll get something together.

HARRIS: Exactly. But there’s so much anticipation and tension around this show, based on the first trailer. I wonder how you feel about challenging your audiences and inviting them into your world now that you’re doing it, not just in a song or on a stage, but on television?

TESFAYE: That’s a good question. I don’t really look at it like I want to challenge my audience. I want to challenge myself. That alone ends up challenging my audience because they’ve been on this ride with me for 13, 14 years. They know that I never do anything the same as I did before. I let them know that at the beginning. Right after House of Balloons, I was like, “I’m going to give you Thursday,” which sounds nothing like House of Balloons and polarized a lot of my fans.

TESFAYE: It works a lot of times and sometimes it doesn’t, but what I know is that I do challenge myself, and this was a challenge. This was something that I’ve always wanted to do. Film and TV, mainly film, has always been kind of the heartbeat of everything I do artistically. If you see my music videos, even sonically, everything is so cinematic and referential to films that I obsess over.

HARRIS: I think that probably the most spins that I had on your records, up until the last couple of years, were all those early mixtapes. How you brought Siouxsie and the Banshees into the world of Canadian nightlife—it became this universe I’d never seen before. That was always so exhilarating to me, and told me that you were the kind of storyteller that aligned with the ways I like to tell stories.

TESFAYE: That’s filmmaking. You watch a Scorsese movie, he’s just playing the music he likes. You hear him play the same Rolling Stones song seven times. [Laughs] You got to write what you know, you got to film what you know, and you got to play what you know. That’s how I attacked all my albums, like a filmmaker.

HARRIS: Who are some of your favorite filmmakers? Who were you thinking about as you were making these albums and now, as you move into a television series?

TESFAYE: I can’t really get into who my favorite filmmakers are. I know that working on The Idol, me and Sam referenced a lot of [Paul] Verhoeven, for sure.

HARRIS: Mm-hmm.

TESFAYE: Right now I’m watching a lot of [Ingmar] Bergman films. I watched Persona yesterday for the tenth time.

HARRIS: You told me about this Japanese filmmaker I was so thrilled by when I was at your house. He’s a Japanese horror filmmaker. Do you remember who?

TESFAYE: Takashi Miike?

HARRIS: Yes, yes, yes. That was a great reference for me to learn, because I’m such a Japanese literature freak but my Japanese cinema knowledge is so slight. But some of the names you were dropping that night when we were going through your basement and looking at your movie area, I was just like, “Oh, wow.”

TESFAYE: Well, I wanted to work at a video store when I was younger. [Laughs]

HARRIS: You did?

TESFAYE: I was that guy. I would walk into one and it’s like, I don’t want to leave.

HARRIS: What was the indie video store that you visited the most as a young guy?

TESFAYE: There was one in downtown Toronto called Queen Video. It was one of those video stores that just had all the indie stuff, all the arthouse stuff. I’d go there and I wouldn’t even buy or rent. I’d just look through everything and obsess over films I’d never seen.

HARRIS: I love it.

TESFAYE: Because I didn’t have money. That’s when I was homeless, around 17, 18. I’d just walk in there and pretend I was going to rent something. The reality was I was just trying to learn about filmmakers and one-ups.

HARRIS: You were so young when your first albums were coming out. That version of your R&B universe was very seedy and dark. It presented an idea of a person that was inaccessible and kind of a bad boy. I remember being so surprised when I met you. I was like, “Oh, wow. He’s just a nice Canadian guy.” [Laughs] Were you always imagining yourself inside of these other worlds, or did your youth as a homeless person make some of these narratives a bit autobiographical?

TESFAYE: Look, it was as complicated as a fucking teenager being homeless in Toronto in 2007, 2008.

HARRIS: Yeah.

TESFAYE: It was a different place back then. Now it’s very overdeveloped, condominiums everywhere. It looks very rich. Before it used to have a lot of character, especially the Queen Street area. Scarborough, where I’m originally from, which is the outskirts of Toronto, was not as fun to grow up in. Me and La Mar [Taylor, Tesfaye’s creative director], when we just left home and went downtown, the struggle–there was something magical about it. There’s something magical about being in this new place and trying to start from the beginning and create your own new narrative as an adult. It was fun.

HARRIS: Yeah.

TESFAYE: Then a couple of years go by, and it’s like, “Oh, shit, this is kind of dark. We need to figure out what we’re doing in life.” [Laughs] But yeah, it was complicated. It was nightlife, it was freedom, and I was a sponge. I wrote what I knew, so it was what I was going through, what he was going through, different stories from that lifetime. I’d just take it all and create this body of work out of it, but it’s not too autobiographical. I sensationalize a lot of it. It’s like creating a movie. You gotta make it a little more exciting than it actually is.

HARRIS: I always say life tends to be on a level three to seven for most normal people. A seven is when you get the call at midnight that something really crazy has happened to your friend. You run over and it’s actually a five. And then in the movie, the call has to be an eight, and when you arrive, it has to be a ten.

TESFAYE: Overreacting is what filmmaking and songwriting is, essentially.

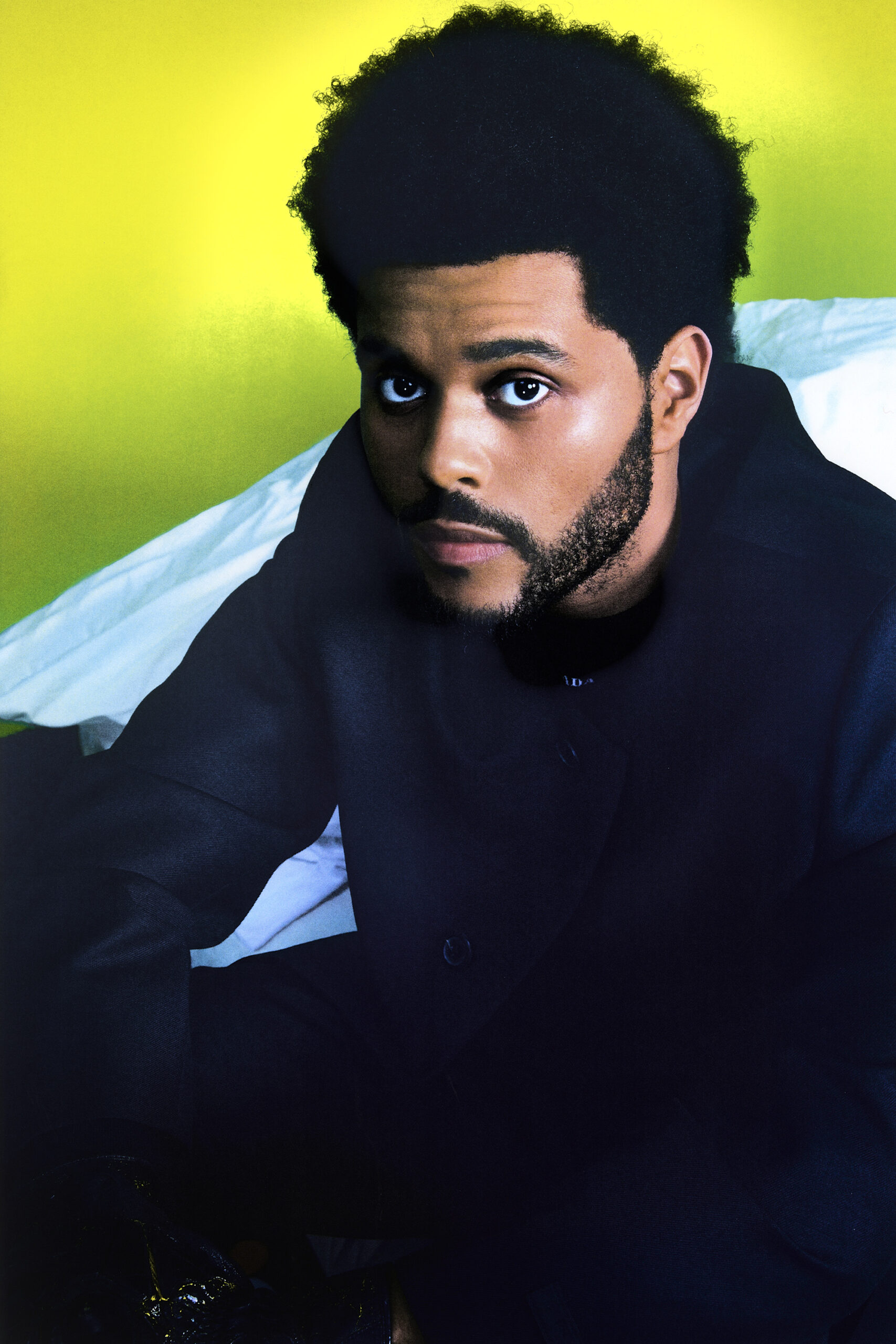

HARRIS: I think a lot about the ways this show, The Idol, has this great exaggeration of so many of our anxieties about those people we meet in Hollywood. You play the type of person that everyone who has spent a significant amount of time in nightlife has an anxiety around. You can’t seem to escape that person. It’s like every time you go out to the club, that person is always there. They always have a table, and they always seem to be friends with someone you know. This guy is always skeezy. He always has the worst style. The hair is always wrong. He is somehow always in the background of pap photos with people and you’re like, “But that person? Okay.” What was your excitement about not only making this character, but playing him?

TESFAYE: I wrote him, but what drew me to play him was just getting to pretend to be someone else. It was a challenge, because The Weeknd, obviously, isn’t me. But I drew a lot from myself to create that character. Tedros is nothing like me.

HARRIS: Yes.

TESFAYE: I got to really play make believe and dive into a character and live in it. It was dark, but it was fun. You’ve seen some of it. It’s quite a fucking ride.

HARRIS: I also feel like you get to make fun of our perceptions of those people and their sleaziness, and even their perception of The Weeknd. Like, you’re dancing in the pilot, and we don’t see The Weeknd dance very often. You’re not that guy onstage. So when you do it in the show, it feels so self-referential and hilarious, especially since some of it is shot in your own house. You also have this really insane bathroom performance that I won’t ruin for anyone, that made me guffaw like no other. It was so insane. I was like, “Oh, he’s going for it.” You really are diving deep into a type of vulnerability that I think must be akin to when you first stepped out of those shadows and said, “Hi, everyone.” Acting is fucking crazy.

TESFAYE: And vulnerability is key in the characters you play, no matter how evil they are. If you can find the vulnerability in them, somehow they become likable.

HARRIS: Yes.

TESFAYE: I got to be free and I got to be vulnerable. And same with Lily [Rose-Depp], man. We got to both just be free and vulnerable because we had a great leader. We had somebody that made us feel comfortable and safe, like we’re all creating something that we could look back on and be proud of. And so big shout-out to Sam and that whole crew. You know Sam, that’s your twin. That’s family right there.

HARRIS: Yeah. What’s really complicated about even doing this interview is that I’ve been a very loud defender of Sam online for a lot of people who don’t know him, his work, and only read things that they never check the sources on. Which is fine, but how has that been for you in the lead-up to the series, having to confront this moment where it feels like people who don’t know you or the people you’re working with have created this entire narrative around the show that feels almost concrete? Are you used to that?

TESFAYE: Yeah. I’m used to it more than someone like Sam, who’s probably a little bit used to it now. And I’m sure Lily, definitely—Lily’s stronger than both of us. But I’ve been judged since the beginning. My stuff’s always kind of been provocative. I understand it’s hard for people to separate that sometimes and that some people want to have an opinion about you, even if it’s not true. As an artist, you have to know that you can’t please everybody, and you have to accept that it comes with the job. You have to remind yourself that everybody that knows you, knows you’re a good person. If you’re going out there trying to prove to people you’re a good person all the time, then it becomes like a dead end. But what I’ve learned is, with time people will learn to understand. But I have thick skin. I’m used to it.

HARRIS: Right.

TESFAYE: But it gets a little complicated for me when there’s more people involved. When it affects other people it hurts me a little bit. That’s what I’m learning about the film business, is that when people start rumors, it really does hurt a lot of other people. A lot of people work hard on these projects. When I’m in my world, and you guys are coming at me, it’s like, alright, cool. I’m a big boy. I can figure it out. But you have 200 people working hard on a project like this, that hurts. Especially when what they’re saying is far from the truth, but, what can you do? What’s your advice? [Laughs]

HARRIS: I don’t have any. What’s your sign?

TESFAYE: Aquarius.

HARRIS: I’m a Gemini, and we’re both air signs, and I think that’s why we have a lot of space for the noise around us. All we have to do is let the work speak for itself, because we’re in this really exciting moment again where at least people are talking about work that’s not just Marvel. They’re looking at these weird television series, plays, books—these works that are dealing with things that all of my favorite writers dealt with. From Kathy Acker to Chip Delany, to Abel Ferrara and Catherine Breillat. They’re taking all of these things that were on the fringe and talking about them in the center of culture.

TESFAYE: I saw Abel Ferrara on that billboard for Saint Laurent driving down Sunset. I was like, who would’ve thought 20, 30 years ago, he would’ve ever been accepted in the mainstream in that type of way?

HARRIS: Exactly. I heard you’re acting in another movie right now. You also just passed Michael Jackson’s Billboard Hot 100 record.

TESFAYE: I think it was a tie. [Laughs]

HARRIS: Are you now an actor-filmmaker-producer, or are you going to try to surpass the tie and become the number one Billboard Hot 100 person?

TESFAYE: Oh, no, no, no. Even with The Idol, the music is just as important as—you probably haven’t heard any of the music. You should come over.

HARRIS: I’ve heard Jocelyn’s [Lily Rose-Depp’s character in The Idol] main song.

TESFAYE: There’s a whole album. I’m not shying away from making music. It’s just adding another element to my already crowded schedule. [Laughs]

HARRIS: I was going to let that be something that someone else talked about. You’ve now changed the game by releasing a television show that is also an album.

TESFAYE: Yeah. I’ve been inspired by The Wall and Purple Rain and when Bowie was doing it, but even films like Shaft, the music is literally telling the story of the film. But I want to take it to the next level. I want to challenge myself and I feel like, as a musician, I’m the best I’ve ever been. But I have ADD. I can’t focus on just that. It’s like, how do I throw a wrench in it?

HARRIS: Right. Another thing I was really curious about, because I’ve been to your very gorgeous home, is how you are now inviting the entire world into your house.

TESFAYE: Well, no, I redid everything. [Laughs] I plastered the walls. I had to make it look different. Let me show you. I don’t know if you remember, but it didn’t look like this.

HARRIS: Oh wow. Yeah. It’s almost brutalist now. What was it like having the whole crew in your home every day for five months?

TESFAYE: I have another place as well, so I just stayed there. But again, I just wasn’t myself for those five months. I was walking into Jocelyn’s house, not mine. I also think I’m wired different. No house has really been a home to me. For most of my career, I’ve been on the road. I really worked hard to get to touring in the stadiums, and the cost was not getting too attached to where I live or where I stay. And I think whatever that instinct was just kicked into gear when I gave my home to this show.

HARRIS: Yeah.

TESFAYE: And everybody was so respectful. You wouldn’t believe it. I guess I’m slowly understanding how big of a gesture that was, to invite all those people into your home.

HARRIS: Nobody said, “Fuck your couch.”

TESFAYE: Maybe Lily said it once. I’m joking. [Laughs] But no, it was a beautiful set and I’m really grateful for everyone that was a part of it. I’m still working with a lot of those people now. We kind of bled over to this next project. I’m proud of what we’ve done, and I know it’s a blessing.

HARRIS: You get to do what you love.

TESFAYE: Yeah. Oh, so the Oscars are today, right? Are you going?

HARRIS: I’m going to Elton John’s house. [Laughs] Are you going to go out tonight?

TESFAYE: No, no, no.

HARRIS: You and Sam are the same. Y’all don’t go out, y’all just stay in your houses.

TESFAYE: No, I actually might go to Sam’s today.

HARRIS: Oh, that’s so funny. I am literally at Sam’s house right now. I’ve been staying here this week.

TESFAYE: Oh nice, I’ll probably see you in a bit.

ARRIS: Okay.

TESFAYE: All right, Jeremy, love you. Thank you for this man.

HARRIS: Love you, too.

———

Barber: Daronn Carr at Blend L.A.

Grooming: Christine Nelli at Kalpana

Set Design: James Rene at Jones Management

Fashion Assistant: Breaunna Trask

Tailor: David Viato

Production: erl Studio

.png)