When Madonna came to the height of her powers in the late 90s and early 00s, it felt as though she had perfected a new mode of pop stardom, making icy, complex and uncannily incisive records such as Ray of Light and Confessions on a Dance Floor. Those albums are powered by a gripping interplay between detachment and intensity; they sound, to me, like attempts to make pop albums without any sense of ego. As if she’s saying: this isn’t a Madonna record, it’s a pop record.

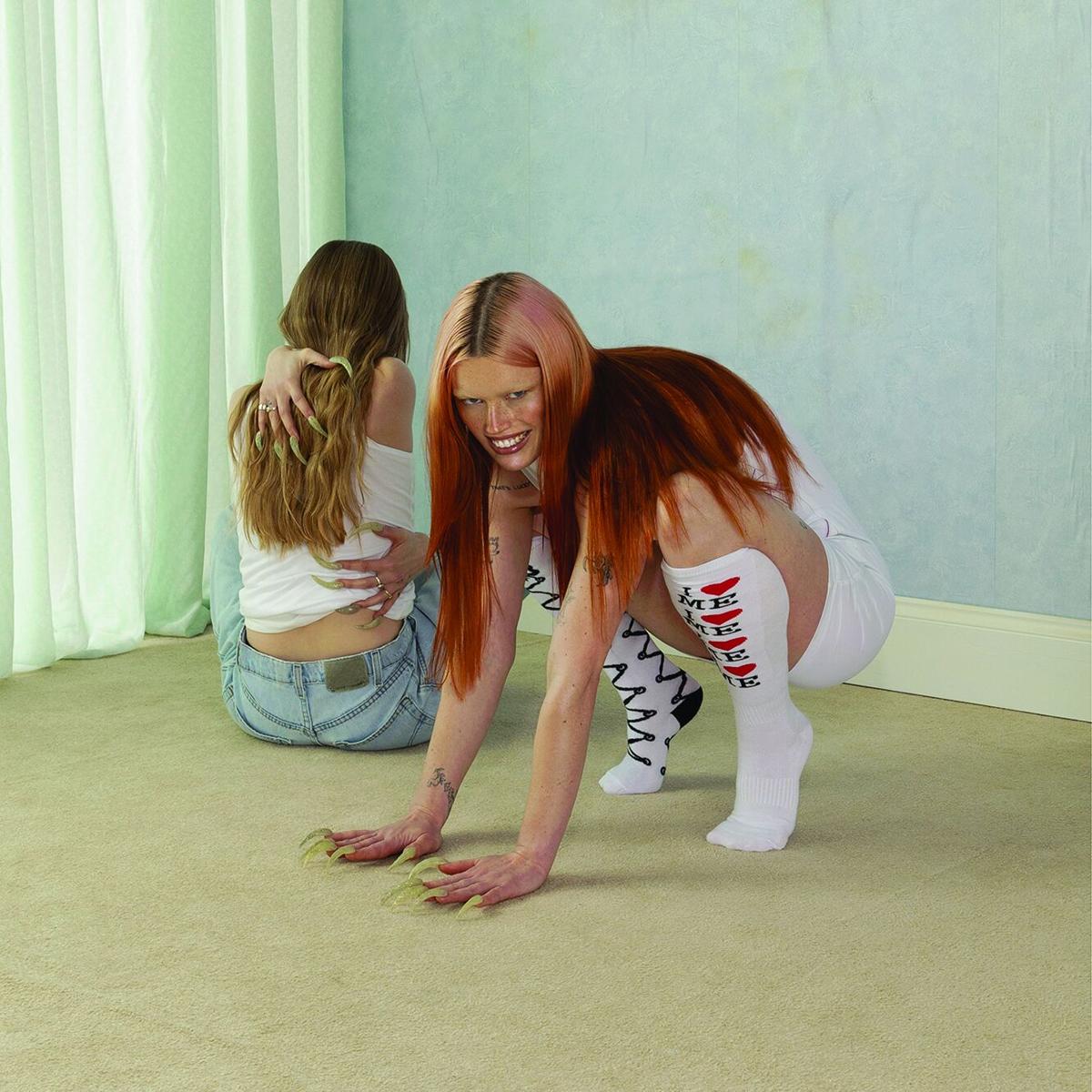

Addison Rae’s exceptional debut album reminds me of that unimpeachable run of Madonna records, understanding that supreme confidence and exceptional taste can sell even the most unusual album. It’s both familiar – Rae is an artist who unapologetically lives and dies by her references – and totally bold: I get the sense that she is less trying to say “this is who I am” as much as “this is what pop should be”.

Rae’s vision of pop is formally traditionalist – she loves big choruses, euphoric key changes, huge builds – but undeniably influenced by her past life as an inhabitant of content-creation HQ Hype House, after her dance videos made her one of the most-followed people on TikTok. The 24-year-old sees no cognitive dissonance in putting together seemingly mismatched aesthetic or emotional sensibilities, a quality that, to me, suggests supreme comfort with the practically dadaist experience of scrolling TikTok’s For You page. Winsome opener New York explores frenetic Jersey club; on Headphones On, a warm-and-fuzzy 90s-style R&B track, she casually tosses off the lyric “wish my mom and dad could’ve been in love” as if it was an intrusive thought she just had to let out.

Although Addison covers a lot of ground musically, every song also sounds uncannily like it came out of the indie-electronica boom of the early 2010s; High Fashion, arguably the best song here, is a pitch-perfect throwback to early James Blake and second-album Mount Kimbie; Diet Pepsi is Lana Del Rey by way of Neon Indian. The record’s remarkable coherence can be chalked up to the fact that Rae worked with the same writer-producer duo, Elvira Anderfjärd and Luka Kloser, on every song – a rare feat for a major-label pop debut, made rarer by the fact that big-budget pop records made exclusively by women are practically nonexistent. But a quick scan of Anderfjärd and Kloser’s credits suggests that Rae is in the driver’s seat here; neither of them has ever made a song as laconically pretty as the EDM-scented Summer Forever, or as girlishly menacing as Fame Is a Gun.

If Addison has a mission statement, it’s on the latter: “Tell me who I am – do I provoke you with my tone of innocence?” she asks at its outset. “Don’t ask too many questions, that is my one suggestion.” It’s an invitation to take Rae’s music at face value – there’s no self-conscious dip into wilful silliness or laborious camp. Most of the time, Rae is stringing together vague abstractions in a way that shuns overinterpretation, like when she sings: “No matter what I try to do / In times like these, it’s how it has to be”, or returns to the phrase “Life’s no fun through clear waters”.

Addison arrives at a fortuitous time: Rae resists the 2020s impulse to intellectualise every pop album and is unencumbered by ham-fisted concepts, Easter eggs or ultra-prescriptive “lore” that tells listeners what to think. Its casually incisive tone suggests Rae might be a great pop flâneuse in the vein of Madonna or Janet Jackson, drifting through the scene with alluring ease and a gimlet eye. But she’d probably tell me I’m overthinking it.