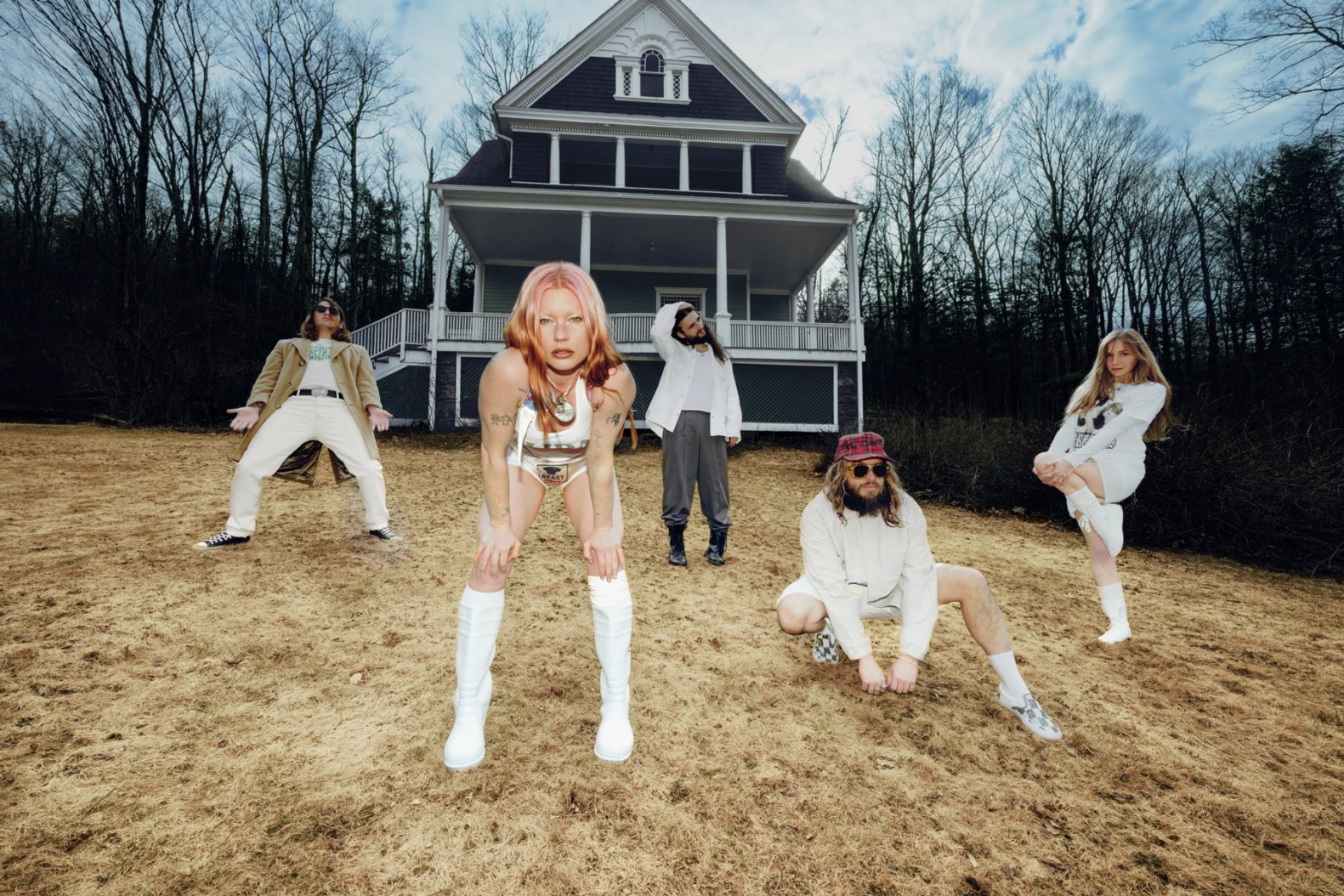

“We’re on our way to the club/Stupid is, stupid does” — whatever party Wet Leg are heading to, it sounds like one worth crashing. The U.K. indie rockers came out of nowhere in 2021 (well, the Isle of Man) to become bona fide international superstars with two devilishly clever singles: “Wet Leg” and “Chaise Longue.” Rhian Teasdale and Hester Chambers banged on their guitars and sneered hysterically cheeky one-liners about the moronic menfolk who cross their paths, with the immortal hook, “Baby, do you wanna come home with me?/I got Buffalo ’66 on DVD.”

Wet Leg started as just a couple of wiseasses fighting off the post-collegiate ennui by writing a few songs for a laugh — as they sang, “I went to school and I got the big D!” They even boasted they came up with the idea to start a band while riding a Ferris wheel. Yet their debut album turned out to be a surprise blockbuster, even in the U.S.A., usually the country where cool British bands go to die. Wet Leg even bagged a couple of Grammys — not bad for a band whose two most famous songs were about vehicular masturbation and snogging groupies in the dressing room. Snappy guitars, casual sarcasm, punk feminist arrogance flipping off the world — what’s not to love?

On their second album, Moisturizer, Wet Leg prove they’ve been partying harder, traveling faster, caring less, and meeting sexier idiots. If you thought they might catch a case of sophomore-slump neurosis, you guessed wrong. They crank up the drum mix, enough to make you suspect they hang out in some pretty sleazy rock clubs these days, for a sound that’s aimed at the floor. “Mangetout” is a damn-near perfect dance-punk summer jam, all pulsing rhythm and brazen confidence and raging hormones. Teasdale comes on strong with a pick-up line for our times: “You think I’m pretty/You think I’m pretty cool/You wanna fuck me?/I know — most people do.” By the end of the song, they’re are chanting, “Get lost forever!”

Moisturizer keeps everything fast and frisky, kicking off with “CPR,” where Teasdale turns lust into a medical emergency, demanding mouth-to-mouth resuscitation with ambulance-siren synth hooks. Since the debut, she’s found herself in a queer relationship for the first time. But as on the debut, every song is funny, chronicling the ups and downs of modern romance. They’ve been stars for a couple of years now, touring with their fan Harry Styles, who did a bang-up version of “Wet Dream” on the BBC. Yet they haven’t cleaned up their young, loud, and snotty act. They’re a full-fledged five-piece band, with their longtime live group and producer/keyboardist Dan Carey. It’s the classic U.K. dance-oriented guitar rush of classic Britpop legends like Elastica or Franz Ferdinand, with plenty of Blondie-worthy attitude.

“Catch These Fists” is about clubbing hard, doing too many drugs, and starting brawls with the losers who try to pick you up when all you want is to dance with your friends. “He don’t get puss, he get the boot,” Teasdale jeers. “I just threw up in my mouth/When he just tried to ask me out.” “Pillow Talk” is a high-speed New Wave ode to romantic lust. “Every night I lick my pillow, I wish I was licking you,” Teasdale sings. “Every night I fuck my pillow, I wish I was fucking you.” Chambers sings lead vocals in a pair of charmers, “Don’t Speak” (not the No Doubt tune) and “Pond Song.”

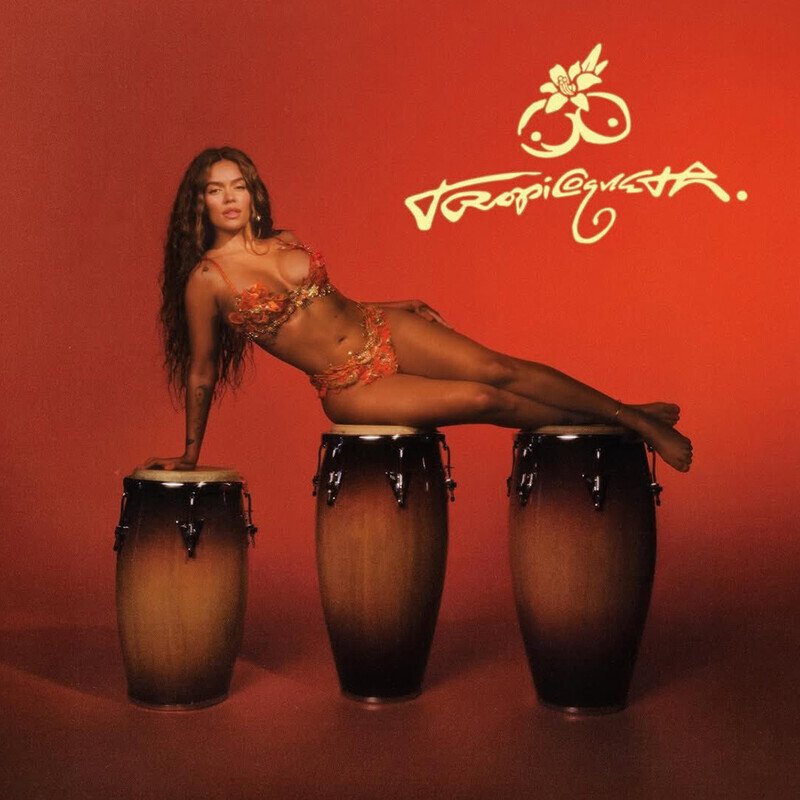

The only dud on the album is the token ballad, “11:21” — slow-motion sensitivity isn’t really Wet Leg’s style. They’re much more at home letting it rip in bangers like “Jennifer’s Body,” “Liquidize,” and “Davina McCall.” The emotions on Moisturizer range from crushed-out bliss (“I’ll be your Shakira, whenever, wherever”) to break-up rage (“You are washed-up, irrelevant, and standing in my light”). But wherever Wet Leg go, they make you want to tag along.