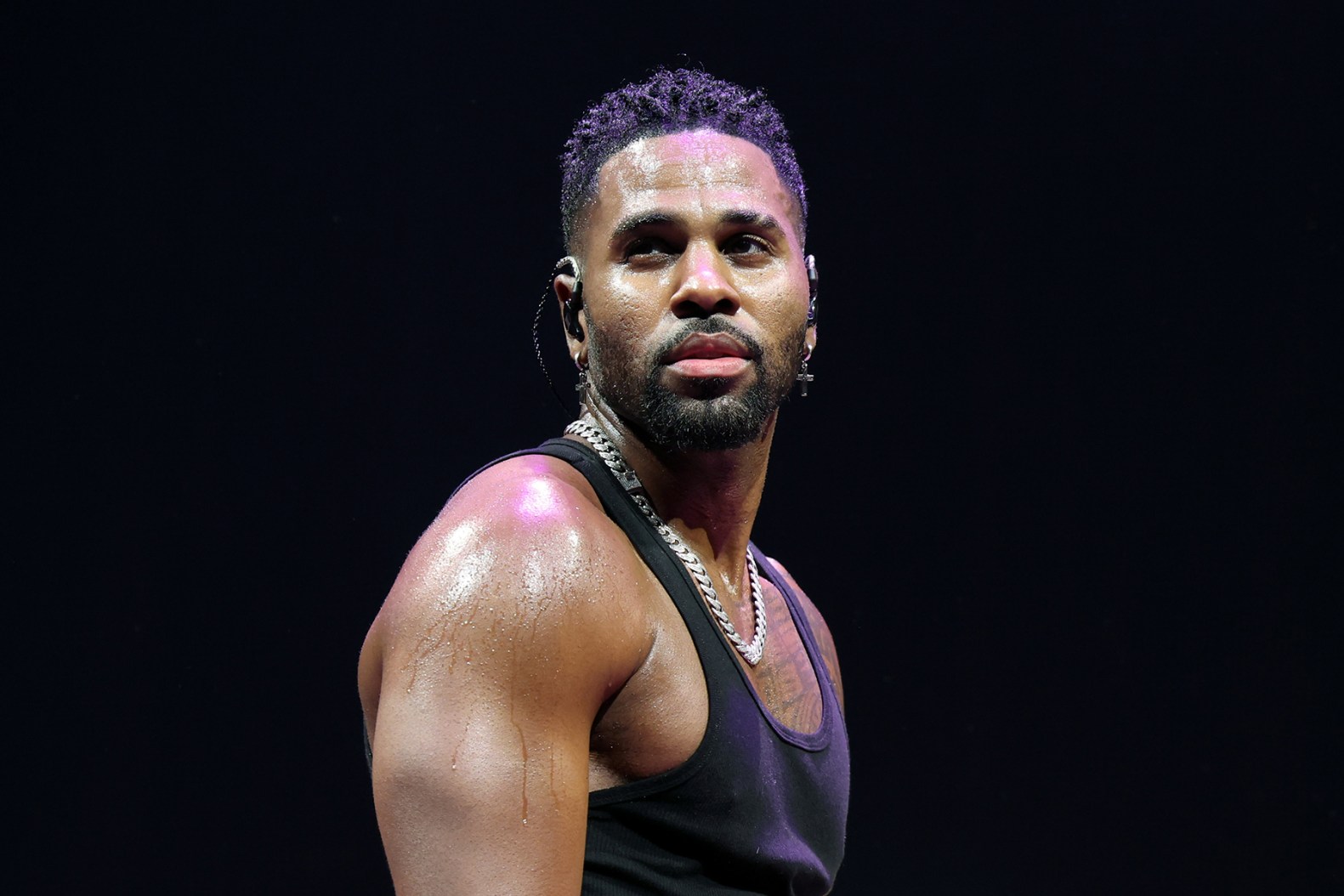

Long-running metal firebrands have matured their sound on LP 17 without sacrificing any of their epic grit

“Remember that patience is no sin,” sings Bruce Dickinson a whole three minutes into Senjutsu’s “The Parchment” — and he’s not kidding, since the song, which is one of the album’s standouts, stretches on for another 10 minutes. Luckily, Iron Maiden are typically not ones to waste listeners’ time. In those 13 minutes, the band blends cinematic Lawrence of Arabia strings with military-march guitar riffing, Dickinson bellows an Olivier Award-worthy monologue about his “primal quest for fear,” and the band’s three(!) guitarists each take turns indulging themselves in solos at times when most conventional heavy-metal bands conclude their tunes (5:01, 6:15, 10:32). But Iron Maiden have never been conventional.

A little more than 40 years ago, Maiden established themselves as one of the most original metal bands to emerge in the wakes of Black Sabbath and Judas Priest. Where most of heavy metal’s forefathers consecrated the genre tag with footslogging doomsaying, Maiden played punkish, nimble cris de coeur declaring victory over nonbelievers or painting Hammer horror vignettes over galloping guitar assaults. About midway into the Eighties, they adopted a more progressive approach to their music — writing longer, more intricate songs with even more fantastical lyrics — without compromising an ounce of metal cred. They also invented the instantly recognizable “Maidenesque” riff — jagged, economical, almost Bach-like melodies that capture minutes of drama in just a few seconds — which have echoed in the music of bands from Metallica to Papa Roach.

In the years since, the band members have been conditioning themselves for their long-distance metal marathons, and now — improbably, when each band member is in his sixties — they’re performing their own impressive Homeric epics on Senjutsu, their 17th album in ways groups half their age only wish they could. The band claims its album title translates from Japanese to “strategy” (or “tactics”), and the fact that Maiden have the patience to strategize their intricate overtures is a privilege of their age.

In fact, Iron Maiden sound their best on Senjutsu when they rise to their burning ambitions — and those sometimes are quite lofty. They recount Belshazzar’s Feast from the Old Testament on “The Writing on the Wall,” reassess Churchill’s shortcomings on “Darkest Hour,” and ruminate on the end of the world on “Senjutsu” and “Days of Future Past.” And they employ all the musical trademarks they’re known for but never self-plagiarize, instead growing each musical idea in a unique way. But the most impressive songs are the most challenging ones.

Although they neither approach anything as grandiose as the 18-minute “Empire of the Clouds,” from their last album, 2015’s The Book of Souls, or the armchair academia of past epics like their interpretation of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” on 1984’s Powerslave, the meatiest songs here show the maturity that Iron Maiden have grown into. “The Time Machine” is a seven-minute ditty that fuses the band’s jig-like guitar motifs with a fist-pumping chorus that stands up to any of their Eighties anthems. “Death of the Celts” weaves lighter, hypnotic musical themes with lilting heavy riffs while Dickinson narrates a tale of Celtic warriors willing to sacrifice themselves for glory, hoping for immortality. And the album’s most stunning song, “Hell on Earth,” builds from a new-age ether into one of Dickinson’s most cutting vocal performances in years as he screams about feeling “lost in anger” around the eight-minute mark. It’s progressive in the most literal sense, as they transition masterfully from one Maidenesque idea to another, one guitar solo to the next and the next and the next, until the song explodes. It’s the victory moment they’ve been singing about for decades; it has just taken decades to get there. If listeners have the stamina — and the patience — Senjutsu is one of the most rewarding and vital albums in Maiden’s catalog.